2. Background¶

This chapter introduces ROS and motivates the additional use case of dynamically reconfiguring ROS systems. Additionally, background on robotics software testing methodology is given, which will form the context and intended use of the method proposed in Implementation.

2.1. ROS¶

The Robot Operating System (ROS) [Macenski2022] is a software framework used by robotics developers and the wider research community to implement reusable software components. It provides valuable abstractions and libraries in the areas of communication between components, system startup, configuration, and introspection. Since its first release in 2010, it has gained wide adoption in the robotics community, with thousands of packages released which provide common functionality in the form of ROS components that can be integrated into complete software stacks. In 2017, the first distribution of ROS 2 was released. This marked a complete redesign and introduced multiple new features explained in detail below, such as Quality of Service (QoS) and the reliance on the Data Distribution Service (DDS) standard for message transport. This work is entirely using ROS 2, and while core concepts have changed little, important details relied upon here do not apply to ROS 1.

This section serves as a brief introduction to the concepts of ROS nodes and topics, which are the basic primitives allowing communication between software modules, as well as the launch system.

2.1.1. Communication¶

Individual software components within a ROS stack are referred to as nodes. A node typically has one distinct functionality, and well-defined inputs and outputs. An example may be an object detector node, which has a camera image as input, and a list of object hypotheses as output. Usually, although not always, each ROS node runs in a dedicated process.

Every ROS Node is a participant in the ROS communication graph, which represents the connections between the inputs and outputs of multiple nodes. Multiple such communication graphs (or “ROS node graphs”) are shown in this work, such as in Fig. 3.1. Communication between nodes is message-based and happens via topics, which are multi-producer, multi-consumer message channels. Nodes can send messages to topics using publishers, and receive messages from topics using subscribers. For each publisher and subscriber, nodes can configure a number of QoS settings, notably, they can request best-effort or reliable transport and can configure queue sizes. For publishing, the application calls a simple Application Programming Interface (API) method of the publisher object, which may directly transfer the message or push the message to a queue for later, asynchronous transmission. Receiving messages from subscribers is realized by registering a callback function with the ROS API.

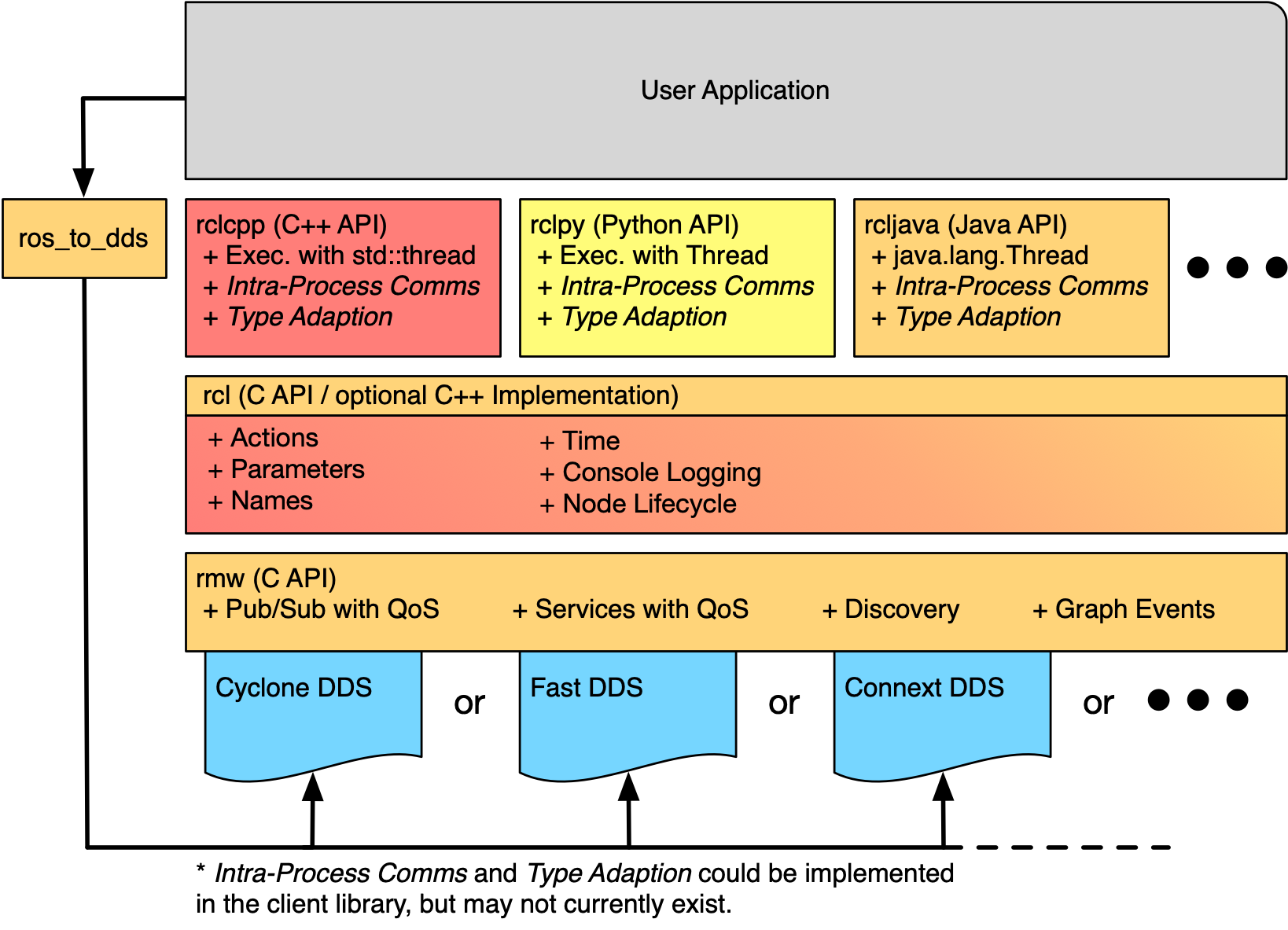

Fig. 2.1 The ROS 2 client library API stack, showing the ability to both support multiple underlying communication middlewares (DDS implementations) and client library bindings in multiple languages. Diagram by the contributors of the ROS 2 documentation on docs.ros.org, licensed under CC BY 4.0.¶

While ROS provides this functionality to the nodes by its API, the underlying functionality of message delivery and node discovery relies on existing implementations of the DDS standard. Fig. 2.1 shows the API stack, with the user code at the very top and the DDS implementation at the bottom. The diagram illustrates that ROS forms a common layer that enables the use of multiple DDS implementations within the middleware (visualized as the blue elements at the bottom of the diagram) and the use of different programming languages for application development (ros client library bindings, directly below the user application in the diagram).

An important aspect of the ROS node communication model is that there is no implicit or explicit back-channel or feedback to the publisher of a message about its (intended) reception. This implies that there exists no concept of back pressure or congestion: If a downstream node is not able to process messages at the rate at which they are published, they will be queued according to the nodes queuing policies (dropping messages if necessary), but upstream nodes producing the messages will not be throttled or otherwise notified.

Individual topics in ROS are identified by name and type, whereby the type is an externally defined structure of named elements which themselves are other ROS types or of a predefined type such as string, numeric, or array types. Topics are created as soon as a node creates a corresponding publisher and subscriber, and two nodes must use the matching name and type to communicate over a topic. In order to allow flexibility when using a node in different environments, the possibility of changing internally used names while starting a node is provided, and referred to as name remapping.

ROS does provide additional mechanisms for communication patterns that do not fit the publish-subscribe model: ROS services provide a method of one-way remote procedure calling between ROS nodes. A ROS node can provide a service by registering a service server, which can then be called by other nodes using a service client. Identically to topics, services are identified by name and type, where the type of a ROS service includes both the request and response type. In contrast to topics, a service call always has a response, which the caller can await.

An additional mechanism built on top of services is actions, which are a ROS way of controlling long-running, interruptible, tasks running within a ROS node. Since these are however fundamentally built atop of services and topics and are not used in the ROS software stack used for evaluation in this work, actions are not of special interest to this work.

2.1.2. ROS Launch¶

Since ROS systems usually consist of multiple nodes, a method for starting an entire robotics software stack is part of the ROS ecosystem. The ROS launch system allows developers to specify actions required to bring up a system in a launch file. Those launch files are typically Python scripts, and actions include launching node processes, including other launch files, or setting parameters.

The possibility to include other launch files allows developers to create subsystems that themselves consist of multiple nodes in a specific configuration. Typically, name remapping is used within the launch file to connect multiple nodes, by setting their internal, generic names for subscribers and publishers to a common name.

In this work, the launch system will be utilized to redirect subscriptions of nodes under test by setting appropriate name remappings, and then including the original launch file as a subsystem, with those parameters applied (further details are provided in Launch System).

2.2. Dynamic Reconfiguration¶

The combination of a specific set of active components, their specific connections, and parameters is referred to as the system configuration. The above section describes how a static, or initial system configuration is specified by the launch file.

Recently, however, research has gone into finding the optimal system configuration depending on the current operating environment, in order to minimize processing requirements while maintaining sufficient system performance [Henning2023].

Such a dynamic reconfiguration may be realized by a dedicated software component, which evaluates the current situation on the basis of available sensor data and environment information. This module may then decide to perform a system reconfiguration when appropriate, and as such may start and stop nodes, or change parameters for running nodes.

To enable this use case, it is necessary to allow changing the system configuration during runtime. ROS allows starting and stopping nodes at any time, and new publishers and subscribers can join existing topics. Parameters within ROS nodes may also be changed during runtime, although the specific node implementation may choose to only read parameters once during startup. While this is generally possible within ROS, the interaction of dynamic reconfiguration with the work presented in this thesis requires special attention (Dynamic Reconfiguration), due to the additional information about system behavior required by the proposed method.

2.3. Software Testing¶

While testing has long been considered an essential part of all software development, it is both especially important and uniquely challenging for robotics, and in particular automotive, software development. Research in autonomous driving aims to improve road safety, but this places the responsibility over the safety of occupants and especially other traffic participants on the software, which makes testing and verification of correct behavior essential.

The type of testing relevant to this work can be classified as integration- or system testing. In the context of ROS software stacks, this amounts to testing one or multiple ROS nodes entirely, in contrast to more specific testing which would directly test an algorithm inside a node, without taking the ROS-specific code into consideration. This work considers performance testing, meaning testing that determines how well the application or system completes the desired task. Additionally, the focus lies explicitly on post-processing testing instead of determining system metrics during runtime. In an autonomous driving context, this amounts to testing using a simulator or recorded data, and not online performance testing during test drives. Other testing methods may verify attributes related to software quality and resilience, but those are not of particular interest in this work. Achieving reproducibility is especially difficult for those testing methods involving multiple components and their interaction and communication, which is what this work aims to address by ensuring deterministic execution.

Regression testing describes the practice of verifying that the performance of the system under test does not fall below previous test executions. As a special case of regression testing, one could verify that the output of the system exactly matches a previous output. This allows the developer to verify that presumably non-functional changes do indeed not modify the observable system behavior, which may have previously been quantitatively evaluated.

2.3.1. Software Performance Metrics in Autonomous Driving¶

A variety of metrics have been proposed for quantitative evaluation and comparison of both the whole-system performance of autonomous driving software stacks, as well as individual software components within such a stack.

One possibility for assessing the entire system performance of an autonomous driving stack is to measure criticality. Criticality is defined by [Neurohr2021] in Definition 1 as “the combined risk of the involved actors when the traffic situation is continued”. In [Westhofen2023], an overview and comparison are given of metrics that measure the criticality of a traffic scenario, many of which use models for driver behavior in order to predict dangerous situations by factors such as small distances or large relative speeds. Notably, the authors of [Westhofen2023] explicitly assume a deterministic testing environment, in which repeating the same inputs yields the same outputs. Since those metrics evaluate the resulting traffic situation, they require running the entire software stack, even when the influence of only a single module on the result is to be determined.

As an example for performance evaluation using application-specific metrics, multiple metrics for a multi-object tracking module are considered. Specifically, the Multiple Object Tracking Precision (MOTP) and Multiple Object Tracking Accuracy (MOTA) metrics as proposed in [Bernardin2008] are used in this work. MOTP is defined as the average distance error \(d\) over all matches \(i\) in each timestep \(t\) (with \(c_t\) the number of matches between detections and ground-truth objects in timestep \(t\))

MOTA provides a measure for how well the tracking algorithm performs with respect to missed objects (\(m\)), false positives (\(fp\)), and track mismatches (\(mme\), i.e. identity switches between identified objects) over the total number of objects \(g_t\), as defined by

Both metrics are calculated over an entire sequence, instead of individual frames.

An additional metric for multi-object tracking applications is the Optimal Subpattern Assignment (OSPA) metric as defined in [Schuhmacher2008]. This metric directly measures the distance between two sets of states with different cardinality, and can thus be calculated for each timestep instead of over an entire sequence. The OSPA metric of order \(p\) is defined for two sets \(X = \{ x_1, \dots, x_m \}\) and \(Y = \{y_1, \dots, y_n\}\) and a distance measure \(d^{(c)}(x,y)\) with cutoff at \(c\) as

In the context of multi-object tracking, the sets \(X\) and \(Y\) represent the estimated tracks at a specific time step and the corresponding ground truth states. The resulting distance may then be interpreted as the average distance between a track and its corresponding ground truth object, with unassigned tracks being assigned the cutoff value \(c\). This metric will be used in Dynamic Reconfiguration to visualize a change in the system performance during a single simulation run, which would not be visible using a metric that is averaged over the entire sequence.

2.3.2. Recorded Data¶

Evaluation and testing of robotics software is often not performed during runtime, but instead using pre-recorded input data. This enables fast iteration and comparison of approaches, methods, or versions thereof with the same inputs. Specific publically available datasets have evolved into de-facto standards, which allows comparison and benchmarking within the entire research community. These datasets are usually accompanied by ground-truth annotations, which are often required to calculate application-specific metrics. Some benchmarks focus on comparing system-level benchmarks and evaluating multiple modules, such as the NuPlan benchmark ([caesar2022nuplan]) which aims to compare the resulting long-term driving behavior in a closed-loop simulation.

The nuScenes dataset ([nuscenes2019]) for example contains camera images as well as lidar and radar measurements from an autonomous vehicle, as well as annotations for class and bounding box of visible objects, and is used extensively to evaluate object detectors in the autonomous-driving context. In those benchmark datasets, input data is commonly available in a format specific to that benchmark. For use within ROS, these formats are often converted to ROS bags, which provide a standard method for storing message data within ROS at a topic level. For direct recording, the ROS bag recorder is available. It subscribes to specified topics, and stores every received message to disk in its serialized format, together with metadata required for replaying the messages. To replay a bag, the ROS bag player creates publishers for every topic recorded in the bag and publishes the messages in the same order as recorded.

Time handling during ROS bag replay differs from the normal execution of a ROS software stack:

Since ROS messages may (and often do) contain timestamps of data acquisition or message creation, and nodes expect to compare them to the current time, a desired functionality is to replay not only the messages but also the time of recording.

This is supported in ROS by delegating timekeeping to the ROS client library as well, which then subscribes to the well-known /clock topic to allow overriding the node’s internal clock.

The ROS bag player then periodically publishes this topic with the time of recording, setting all node clocks.

2.3.3. Simulation¶

Using a simulator is another method for off-robot software testing besides using recorded sensor data. A simulator allows for closed-loop execution of the software stack or module under test. This allows the evaluation of more modules, such as planning or control algorithms, which directly and immediately influence the robot’s behavior.

A large number of robotics simulators have been developed, each with specific use cases and goals, even in the context of autonomous vehicles alone: General robotics simulators such as Gazebo ([gazebo]) feature a general physics engine capable of simulating arbitrary robots with involved locomotion techniques and a large variety of sensors. Application-specific simulators such as CARLA ([carla]) utilize existing rendering engines to simulate typical sensors such as cameras and LIDAR in high fidelity, and use specific models for simulation of relevant objects such as vehicles and other traffic participants. Higher-level simulation tools do not simulate individual sensor measurements, but the output of detectors, greatly reducing the computational effort at the cost of not being able to use and test specific detection modules.

The simulator used for evaluation in this work is the DeepSIL framework introduced in [Strohbeck2021]. While the specific deep-learning-based trajectory prediction features are not used here, it provides a representative baseline for a simulator in use for autonomous-driving development, in order to evaluate the integration effort of the proposed framework. In the configuration used for evaluation, DeepSIL generates detections from virtual sensors and detection algorithms and simulates vehicles either by using a driver model or using control inputs generated by external planning and control modules. The simulated detections, simulated vehicle state estimation as well as ground truth object states are published to the software under test via ROS topics.