4. Evaluation¶

In this chapter, the functionality and applicability of the proposed framework will be evaluated. In Verification of Functionality, the behavior with and without the orchestrator in the minimal examples presented in Sources of Nondeterministic Callback Sequences is verified. System Setup then introduces the experimental setup used for further evaluation, which represents a real use case utilizing an existing autonomous-driving software stack. The process of integrating the existing components with the orchestrator is covered in System Integration, followed by an evaluation and discussion of using the orchestrator in the presented use case in Application to Existing Scenario. In Execution-Time Impact, the impact of using the orchestrator on execution time is explicitly assessed, and approaches for improvement are discussed.

4.1. Verification of Functionality¶

In order to verify the functionality of the orchestrator, without depending on existing ROS node implementations, individual test cases for specific sources of nondeterminism as well as a combined mockup of an autonomous driving software stack were developed. In the following, each of the examples containing sources of nondeterministic callback sequences identified in Sources of Nondeterministic Callback Sequences is individually evaluated.

4.1.1. Lost or Reordered Messages¶

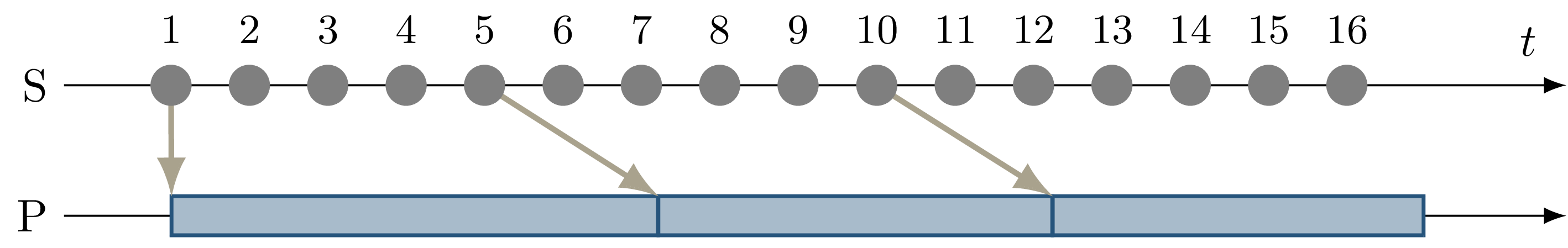

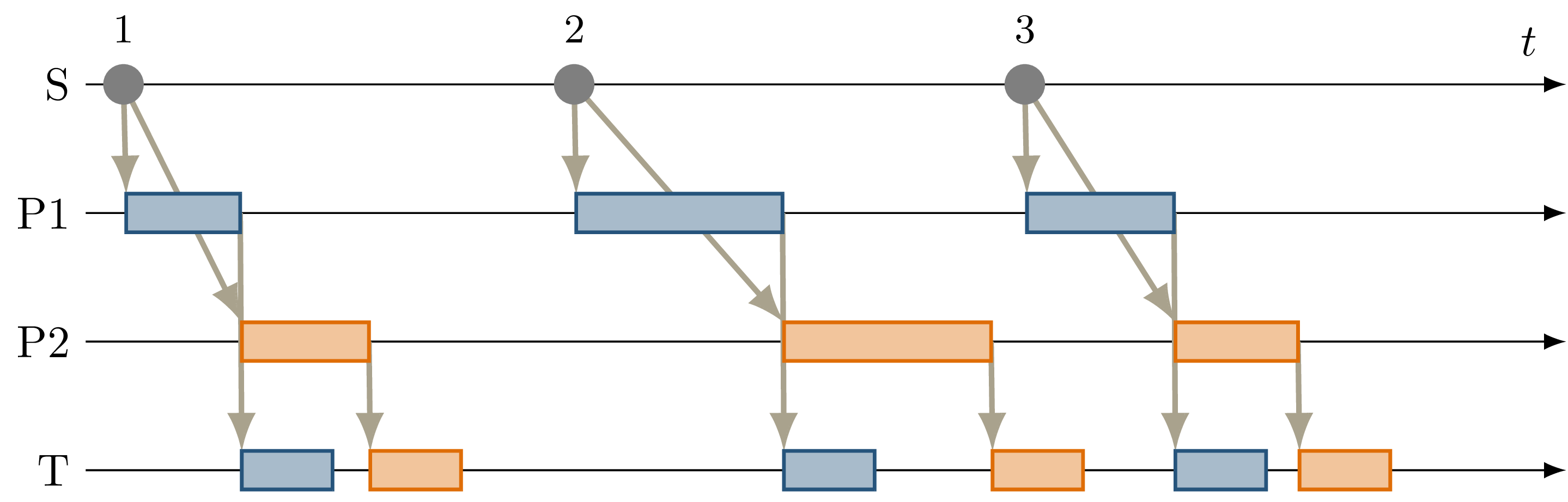

To verify that the problem of lost messages due to overflowing subscriber queues, as introduced in Lost or Reordered Messages, is solved by the orchestrator, a test case was set up: A data source \(S\) publishes messages at a fixed frequency. The messages are received by the node under test \(P\), which has a fixed queue size (of three messages in this example), and a varying processing time that on average is significantly slower than the period of message publishing. After processing, \(P\) publishes the result on a different topic. This behavior might correspond to a simulator running at a fixed frequency, and a computationally expensive processing component such as a perception module, running on a resource-constrained system.

Fig. 4.1 Sequence diagram showing dropped messages due to subscriber queue overflow, with a subscriber queue size of 3 at \(P\). The corresponding ROS graph is shown in Fig. 3.2.¶

Fig. 4.1 shows the sequence of events when running this test: The first timeline shows the periodic publishing of input messages by \(S\). The second timeline shows the callback duration of node \(P\). It can be seen that once the processing of the first message finishes, processing immediately continues for message 5, which is the third-recent message published at that point in time, skipping messages 2, 3, and 4 which were published during processing. During the processing of message 5, four further messages are discarded. The exact number of skipped messages depends on the callback duration, which in this case is deliberately randomized but is usually highly dependent on external factors such as system load.

Fig. 4.2 Sequence diagram showing a slowdown of the data source to prevent dropping messages by overflowing the subscriber queue.¶

When using the orchestrator, the message publisher is still configured to the same publishing rate, but waits for the orchestrator before publishing each message. Fig. 4.2 shows that each message is now processed, regardless of callback duration. This necessarily slows down the data source, which can not be avoided without risking dropping messages from the subscription queue at the receiving node.

By only sending messages to a node once the processing of the previous message is completed, reordering of messages by the middleware is also prevented. This is not explicitly demonstrated here but follows immediately from the fact that only one message per topic is being transmitted at any point in time.

4.1.2. Inputs From Parallel Processing Chains¶

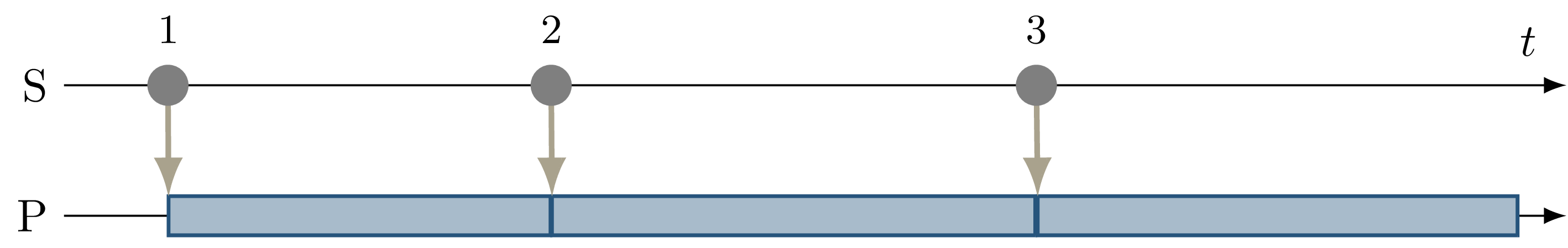

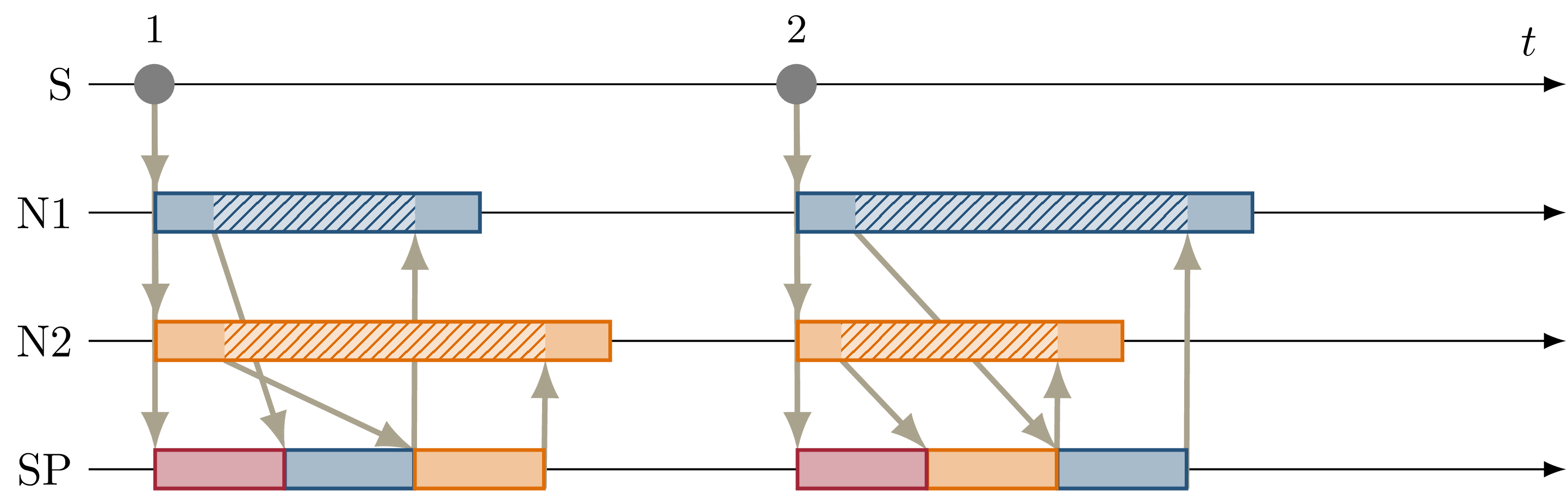

Fig. 4.3 Sequence diagram showing the execution of two parallel processing nodes \(P1\) and \(P2\) with nondeterministic processing time. This results in a nondeterministic callback order at \(T\), which subscribes to the outputs of both chains. The corresponding ROS graph is shown in Fig. 3.4.¶

To verify deterministic callback execution at a node with multiple parallel inputs, the example introduced in Inputs From Parallel Processing Chains with the ROS graph shown in Fig. 3.4 is realized. Fig. 4.3 shows all callback invocations resulting from two inputs from \(S\). Without the orchestrator, the combination of nondeterministic transmission latency and variable duration of callback execution at \(P1\) and \(P2\) results in a nondeterministic execution order of both callbacks at \(T\) resulting from one input from \(S\).

For input 1, \(P1\) finishes processing before \(P2\), and no significant transmission latency occurs, which causes \(T\) to process the message on \(D1\) before \(D2\). Following input 2, \(P2\) is slightly faster than \(P1\) resulting in a different callback order compared to the first input.

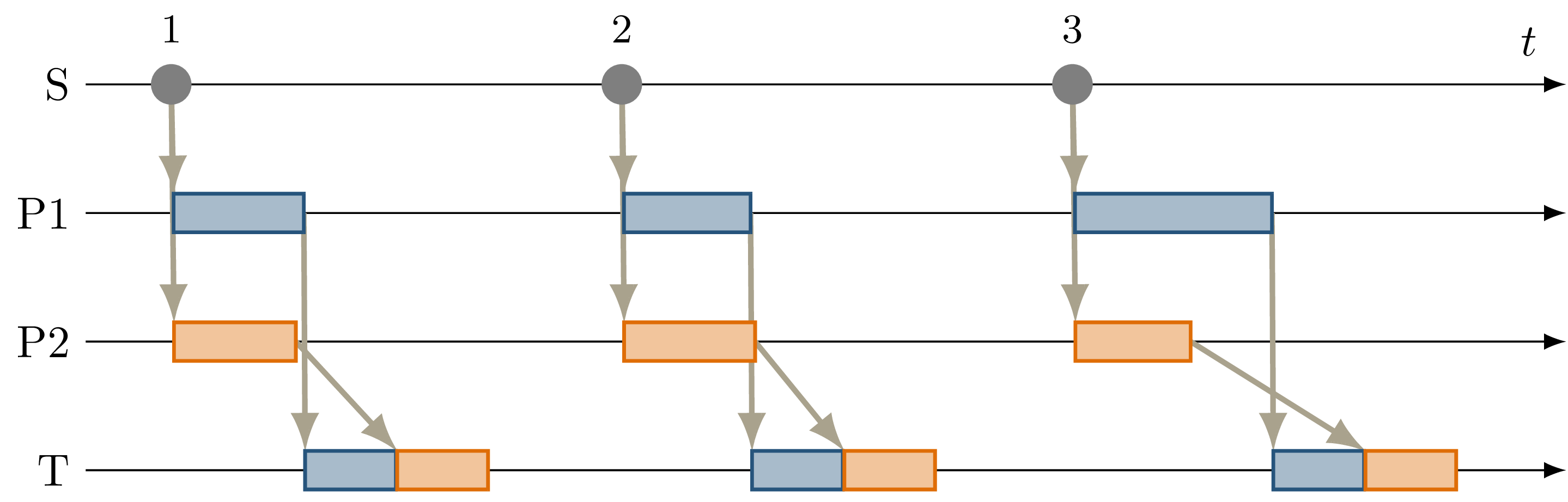

Fig. 4.4 Sequence diagram showing a deterministic callback order at \(T\) despite nondeterministic callback durations at \(P1\) and \(P2\) as an effect of the orchestrator on the behavior shown in Fig. 4.3.¶

Using the orchestrator, the callback order changes, as visualized in Fig. 4.4. For the first and third data input, \(P1\) requires more processing time than \(P2\). This would ordinarily allow the \(D2\) callback at \(T\) to execute before the \(D1\) callback. The orchestrator however ensures a deterministic callback order at \(T\) for every data input from \(S\), by buffering the \(D2\) message until \(T\) finishes processing \(D1\). Note that the orchestrator does not implement a specific callback order defined by the node or externally. It only ensures that the order is consistent over multiple executions. The actual order results from the order in which nodes and callbacks are listed in configuration files, but this is not intended to be adjusted by the user. If a node requires a distinct receive order, it must implement appropriate ordering internally, to ensure correct operation without the orchestrator. From the point of the orchestrator, consistently ordering \(P2\) before \(P1\) would have also been a valid solution.

4.1.3. Multiple Publishers on the Same Topic¶

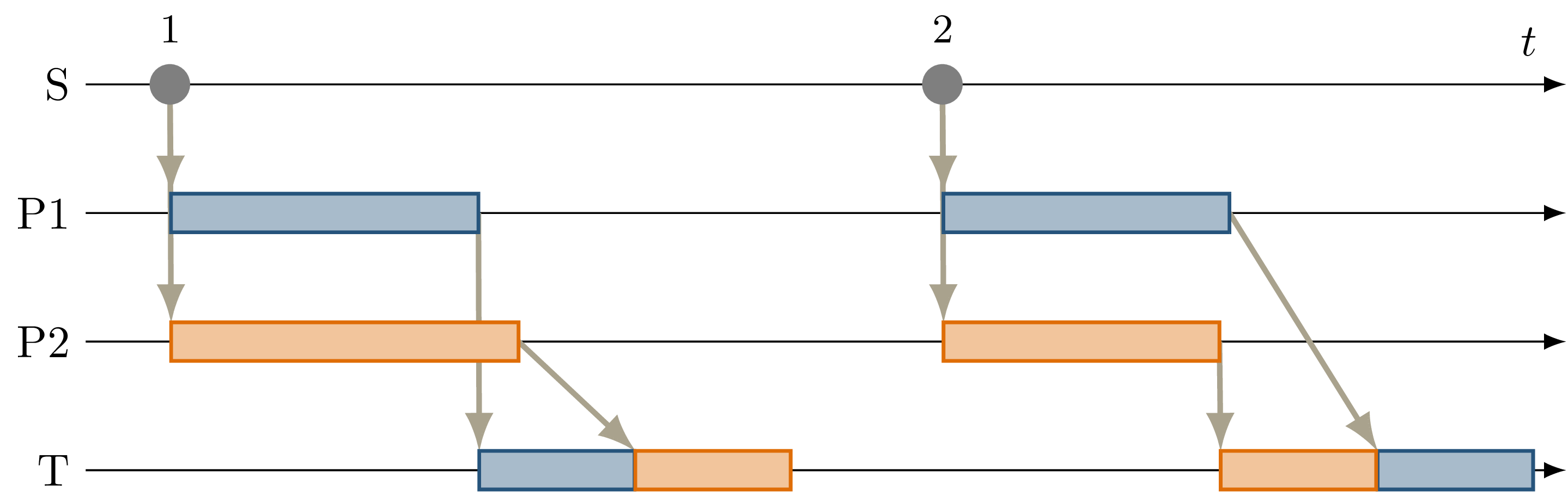

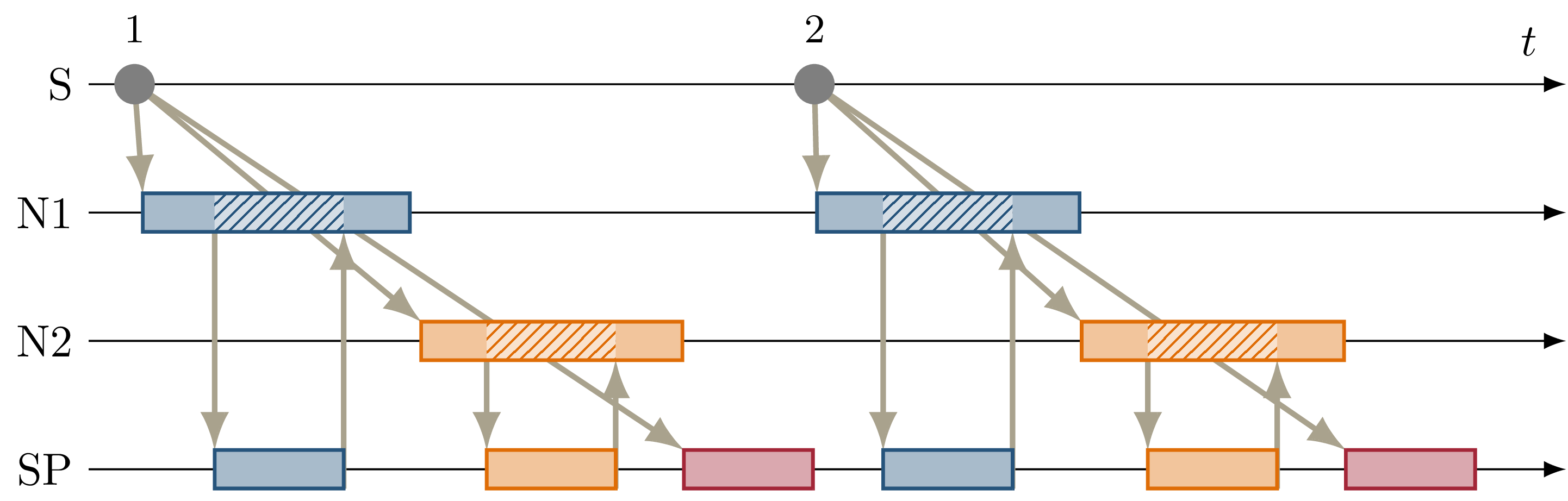

Fig. 4.5 Sequence diagram showing serialized callback executions of nodes \(P1\) and \(P2\), which is required to achieve a deterministic callback order at \(T\) in this example, since \(P1\) and \(P2\) use the same output topic. The corresponding ROS graph is shown in Fig. 3.5.¶

This example extends the previous scenario from Inputs From Parallel Processing Chains such that both processing nodes publish their result on the same topic, corresponding to the example introduced in Multiple Publishers on the Same Topic, with the ROS graph shown in Fig. 3.5. Again, this results in nondeterministic callback order at \(T\), with a callback order identical to the previous case shown in Fig. 4.3. In this case, both callback executions at \(T\) are of the same callback, while previously two distinct callbacks were executed once each.

Because only node inputs are intercepted, this scenario requires serializing the callbacks at \(P1\) and \(P2\). Fig. 4.5 shows the resulting callback sequence when using the orchestrator. By ensuring that processing at \(P2\) only starts after the output from \(P1\) is received, reordering of the messages on \(D\) is prevented. Note that while the different colors of the callbacks at \(T\) correspond to the sources of the corresponding input, both inputs cause the same subscription callback to be executed at the node. Generally, the node would not be able to determine the source of the input message.

Since the processing time of \(P2\) is longer than the processing time of the first callback at \(T\) in this example, the orchestrator causes a larger overhead for this node graph compared to the previous one. \(P2\) starts processing simultaneously to the first \(T\) callback, causing \(T\) to be idle between the completion of the first callback and the completion of processing at \(P2\). It should be noted, however, that even though the total processing time exceeds the input frequency of \(S\) for input 2, the data source was not required to slow down. Fig. 4.5 shows that \(T\) is still running while \(P1\) processes input 3. This kind of “pipelining” happens implicitly because the callback execution at \(P1\) has no dependency on the callback at \(T\), and by eagerly allowing inputs from \(S\). In the current implementation, the orchestrator requests the publishing of the next message by the data provider as soon as the processing of the last input on the same topic has started. In the case of a time input, the input is requested as soon as no actions remain which are still waiting on an input of a previous time update. Both kinds of input may additionally be delayed if the system is pending dynamic reconfiguration, or if a callback is still running that may cause a reconfiguration at the end of the current timestep.

4.1.4. Parallel Service Calls¶

Fig. 4.6 Sequence diagram showing the parallel execution of callbacks at \(N1\) and \(N2\). The hatched area within the callback shows the duration of service calls, which are made to a service provided by \(SP\), upwards arrows represent responses to service calls. The variable timing of the service calls results in a nondeterministic callback order at \(SP\). The corresponding ROS graph is shown in Fig. 3.6.¶

Fig. 3.6 shows the node setup for this example, which has been identified in Parallel Service Calls. A single message triggers a callback at three nodes, one of which (\(SP\)) also provides a ROS service. The two other nodes \(N1\) and \(N2\) call the provided service during callback execution. The resulting order of all three callbacks at \(SP\) in response to a single message input is nondeterministic, as shown in Fig. 4.6. Since the orchestrator only controls service calls by controlling the callback they originate from, it is necessary to serialize all callbacks interacting with the service, which in this case are the message callbacks at \(N1\), \(N2\), and \(SP\).

Fig. 4.7 Sequence diagram showing the serialized callbacks from Fig. 4.6. Serialization of the callbacks at \(N1\) and \(N2\) leads to a deterministic callback order at \(SP\).¶

The resulting callback sequence is shown in Fig. 4.7. By serializing the callbacks at \(N1\) and \(N2\), the order of service callbacks at \(SP\) is now fixed. In this example, it is again apparent that parallel execution of the \(N1\) and \(N2\) callbacks might be possible while still maintaining a deterministic callback order at \(SP\). This limitation is discussed in detail in Discussion.

4.1.5. Discussion¶

The ability of the orchestrator to ensure a deterministic callback sequence at all nodes has been shown for the minimal nondeterministic examples which were identified in Sources of Nondeterministic Callback Sequences. While all examples show successful deterministic execution, some limitations and possible improvements in parallel callback execution and thereby execution time are apparent and will be discussed in the following.

In the case of concurrent callbacks which publish on the same topic, parallelism could further be improved by extending the topic interception strategy.

Currently, only the input topics of each node are intercepted by the orchestrator, the output topics are not changed.

If the output topics of nodes were also remapped to individual topics, all SAME_TOPIC dependencies would be eliminated.

In the example from Fig. 4.4, this would again allow the concurrent callbacks \(P1\) and \(P2\) to execute in parallel, with each output being individually buffered at the orchestrator.

The individually and uniquely buffered outputs could then be forwarded to \(T\) in a deterministic order, effectively resulting in a callback execution behavior as in Inputs From Parallel Processing Chains.

The last example of concurrent service calls (Parallel Service Calls) also shows how this method of ensuring deterministic execution comes with a significant runtime penalty. Here, the orchestrator now requires all callbacks to execute sequentially, while previously all callbacks started executing in parallel, with the only point of synchronization being the service provider, depending on available parallel callback execution within the node. An important factor determining the impact of this is the proportion of service-call duration to total callback duration for the calling nodes. If the service call is expected to take only a small fraction of the entire callback duration, a large improvement in execution time could be gained by allowing parallel execution of the callbacks \(N1\) and \(N2\), which both call the service. This might be possible by explicitly controlling service calls directly instead of controlling the entire callback executing that call. In the example shown in Fig. 4.7, serializing only the service calls would allow the portion of the \(N2\) callback before the service call to execute concurrently to \(N1\), and the portion after the service call to overlap with the message callback at \(SP\).

Another possible extension to improve parallelism in scenarios involving service calls is to allow specifying that some actions might interact with the service provider without modifying its state. Currently, all actions interacting with the service (by running at the same node, or calling the service) are assumed to modify the service provider state. To ensure deterministic execution, synchronization between non-modifying actions is however not required. If an action only inspects the service providers’ state without modifying it, the order with respect to other such actions would not influence its result. Thus, it would suffice to synchronize non-modifying actions with previous modifying actions, instead of all previous actions.

In Inputs From Parallel Processing Chains, it was identified that although the callback order at each node is not deterministic, a different order of callbacks in response to a single input might be expected during normal operation. This does not reduce the applicability of the orchestrator, since nodes that explicitly require a specific callback order must implement measures to ensure that anyways. It is however still desirable to keep the system behavior when using the orchestrator as close as possible to the expected or usual system behavior without the orchestrator. One proposed future addition is thus allowing nodes to optionally specify an expected callback duration in the corresponding configuration file. This information may then be used by the orchestrator to establish a more realistic callback ordering.

4.2. System Setup¶

In the following, the integration of the orchestrator with parts of an already existing autonomous driving software stack is evaluated. This section introduces the system setup and example use case, which will be utilized in System Integration, Application to Existing Scenario.

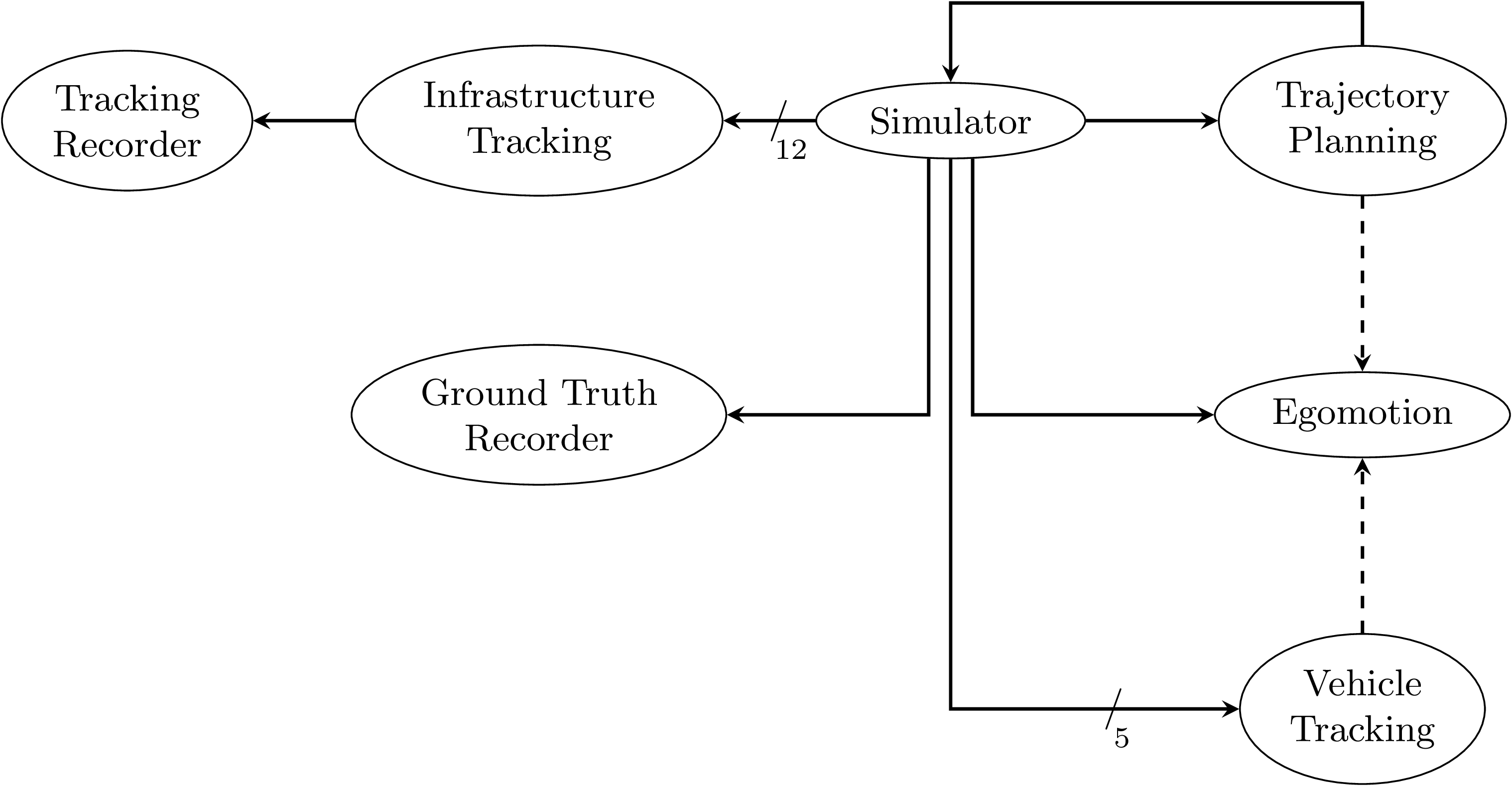

Fig. 4.8 Node graph of the system setup used within this chapter. The connections between the simulator and both tracking nodes represent multiple parallel ROS topics. Dashed arrows show potential service calls.¶

In this use case, the aim is to calculate metrics on the performance of a multi-object tracking module, which tracks vehicles that pass an intersection using infrastructure-mounted sensors. The ROS graph of the setup is shown in Fig. 4.8. The software stack consists of this tracking module, as well as components required to autonomously control one of the vehicles passing the intersection in the test scenario. A simulator provides measurements in the form of (possibly incomplete) bounding boxes and object class estimations, simulating both the sensor itself as well as an object detection algorithm. Alternatively, the same measurements are played back from a ROS bag. The tracking module receives measurements on a total of 12 individual topics for each sensor. Outputs from the tracking module, as well as ground truth object states provided by the simulator, are recorded by dedicated recorder nodes. This allows later post-processing and evaluation.

The part of the software stack controlling the autonomous vehicle consists of a second instance of the tracking module, a component estimating the vehicle’s ego-motion as well as a trajectory planning and control module. The vehicle-local tracking module receives measurements from five simulated on-vehicle sensors similar to the infrastructure tracking module. The planning module receives information about the vehicle state from the simulator and produces acceleration and steering angle commands which are fed back to the simulator. Both the planning and local tracking modules may call the ego-motion service provided by the corresponding node while executing any callback. The other vehicles present in the scenario are fully controlled by the simulator.

The simulation is run until the controlled vehicle reaches a predefined area. When using recorded measurement data from a ROS bag, the scenario ends once every recorded measurement has been processed. The recorded results of the tracking module and the recorded ground truth data are then used to calculate application-specific metrics to assess the performance of the multi-object tracking algorithm.

4.3. System Integration¶

To determine the feasibility of integrating the proposed framework into existing software, the framework was applied to the scenario for testing a multi-object tracking module introduced in System Setup. In this section, the necessary modifications to each existing component are discussed. Simulator, ROS Bag Player will cover the integration of both “data provider” components, a simulator, and the ROS bag player, which will contain the orchestrator. ROS Nodes covers the integration of the ROS nodes present in the test scenario.

4.3.1. Simulator¶

The orchestrator represents an individual component (see Controlling Callback Invocations), but is located within the same process as the data provider, which in this case is the simulator.

The orchestrator component is instantiated within the simulator and then provides an API that the simulator must call at specific points to ensure deterministic execution.

To instantiate and start the orchestrator, the simulator must also provide the orchestrator with the appropriate launch configuration.

All API calls are of the form wait_until_<condition> and usually return a Future object that must be awaited before executing the corresponding actions.

The wait_until_publish_allowed function must be inserted before publishing any ROS message on any topic.

Before publishing a /clock message, the new time must be provided to the orchestrator using the dedicated wait_until_time_publish_allowed API call, which is required for the orchestrator to prepare for eventual timer callbacks.

Before changing the internal simulation state, the wait_until_dataprovider_state_update_allowed method must be called.

This usually happens by performing a simulation timestep, and this method ensures synchronizing this timestep with expected inputs present in a closed-loop simulation, such as vehicle control inputs.

The wait_until_pending_actions_complete method is used to ensure all callbacks finish cleanly once the simulation is done.

To enable closed-loop simulation, the simulator must accept some input from the software under test, such as a control signal for an autonomous vehicle in this case. This implies a subscription callback, which must be described in a node configuration file. If this callback does not publish any further messages, a status message must be published instead.

4.3.2. ROS Bag Player¶

ROS already provides a ROS bag player, which could be modified to include the orchestrator.

Modifying the official ROS bag player would have the advantage of keeping access to the large set of features already implemented, and preserving the known user interface.

Some aspects of the official player increase the integration effort considerably, however.

Specifically, publishing of the /clock topic is asynchronous to message playback and at a fixed rate.

While this has some advantages for interactive use, it interferes with deterministic execution and would require a significant change in design to accommodate the orchestrator.

Furthermore, as with the initial architecture considerations of the orchestrator, it is undesirable to fork existing ROS components and maintain alternative versions, as this creates an additional maintenance burden and might prevent the easy adoption of new upstream features.

Thus, a dedicated ROS bag player is implemented for use with the orchestrator instead of modifying the existing player.

This does not have the same feature set as the official player but allows for evaluation of this use case with a reasonable implementation effort.

To integrate the orchestrator, the ROS bag player requires the same adaptation as the simulator, except for the wait_until_dataprovider_state_update_allowed call which is not applicable without closed-loop execution.

Besides deterministic execution, a new feature is reliable faster-than-realtime execution, details of which are discussed in Execution-Time Impact.

4.3.3. ROS Nodes¶

The individual ROS nodes of the software stack under test are the primary concern regarding implementation effort, as there is usually a large number of ROS nodes, and new ROS nodes may be created or integrated regularly.

The integration effort of a ROS node depends on how well the node already matches the assumptions made and required by the orchestrator: The orchestrator assumes that all processing in a node happens in a subscription or timer callback, and that each callback publishes at most one message on each configured output topic. For callbacks without any outputs or callbacks that sporadically omit outputs, a status message must be published instead (see Callback Outputs).

4.3.4. Planning Module¶

The integration effort of the trajectory planning and control module is significant because the module violates the assumption that all processing happens in timer and subscription callbacks.

The planning module contains two planning loops: A high-level planning step runs in a dedicated thread as often as possible. A low-level planner runs separately at a fixed frequency. Handling incoming ROS messages happens asynchronously with the planning steps in a third thread.

While this architecture may have some advantages for runtime performance, it prevents external control via the orchestrator. This represents an inherent limitation for the orchestrator. Publishing of messages from outside a ROS callback is not able to be supported in any way, since it can not be anticipated in advance, making it impossible to integrate into the callback graph and synchronize it with other callbacks (see Ensuring Sequence Determinism Using Callback Graphs). In order to ensure compatibility with the orchestrator, an optional mode has been introduced in which both planning loops are replaced with ROS timers.

This does make the planning module compatible with the orchestrator, but introduces a problem that should have explicitly been avoided by the specific software architecture chosen: It runs the planning module in a completely different mode when using the orchestrator than without using the orchestrator. This reduces the relevance of testing inside the orchestrator framework since specific problems and behaviors might only occur with the manual planning loop.

It might be possible in some cases to change the node in a way such that the usual mode of execution is compatible with the orchestrator, and thus avoids the problem of two discrete modes, but this is not possible in general. In the case of the trajectory planning module, for example, this is not desirable due to the integration of the planning loop with a graphical user interface that is used to interactively change planner parameters and to introspect the current planner state.

4.3.5. Tracking Module¶

While the tracking module does only process data within ROS subscription callbacks, the input-output behavior is still not straightforward: The tracking module employs a sophisticated queueing system, which aims to form batches of inputs from both synchronized and unsynchronized sensors, while also supporting dynamic addition and removal of sensors. Additionally, while processing is always triggered by an incoming message, the processing itself happens in a dedicated thread in order to allow the simultaneous processing of ROS messages.

The input-output behavior itself is configurable such that only the reception of specific sensor inputs cause the processing and publishing of a “tracks” output message.

This is done to limit the output rate and reduce processing requirements.

Due to the queueing, this does however not imply that reception of the configured input immediately causes an output to appear.

It may be the case that additional inputs are required to produce the expected output.

This behavior can however still be handled by the node configuration without requiring major modification to the tracking module:

The node configuration was modified such that any input may cause an output to be published.

Then, the processing method was adapted such that a status message is published that explicitly excludes the tracks output using the omitted_outputs field when no tracks will be published.

In some circumstances, specifically following dropped messages, the queueing additionally results in multiple outputs in a single callback.

This behavior is described in detail in ROS Bag and is not currently supported by the orchestrator.

While this is a pragmatic solution for describing the otherwise hard to statically describe input-output behavior of the tracking module, declaring more output topics than necessary for a callback is usually undesired:

Subsequent callbacks which actually publish a message on the specified topic need to wait for this callback to complete due to a false SAME_TOPIC dependency.

Additionally, the callback graph will contain possibly many actions resulting from the anticipated output.

Those actions are then again false dependencies for subsequent actions, not only as SAME_TOPIC dependencies but also SAME_NODE and SERVICE_GROUP edges.

These false dependencies might reduce the number of callbacks able to execute in parallel and might force callback executions to be delayed more than necessary to ensure deterministic execution.

Once a status message is received which specifies that the output message will not be published, the additional actions are removed, which then allows the execution of dependent actions.

4.3.6. Recorder Node and Ego-Motion Estimation¶

Both the nodes for recording the output of the tracking module and the ego-motion estimation match the assumptions made by the orchestrator and require very little integration effort, although some modification was necessary. Both nodes only have topic input callbacks that would usually not cause any message to be published, requiring the publishing of a status message to inform the orchestrator of callback completion.

The ego-motion module is the only node in the experimental setup offering a service used during the evaluation. This does however not require any modification within the node, as service calls are controlled by controlling the originating callbacks. It is required however to list the service in the node configuration, to ensure a deterministic order between service calls and topic-input callbacks at the node.

4.3.7. Discussion¶

In Design Goals, the design goals towards the integration of existing nodes were established as minimizing the required modification to nodes, maintaining functionality without the orchestrator, and allowing for external nodes to be integrated without modifying their source code.

The implemented approach meets these goals to varying degrees. The integration of existing components with the orchestrator requires a varying amount of effort, depending primarily on how well the component matches assumptions made by the orchestrator. ROS nodes that fully comply with the assumptions made by the orchestrator and always publish every configured output require only a configuration file describing the node’s behavior, which also works for external nodes without access to or modification of their source code. Nodes that have callbacks without any output and nodes that may omit some or all configured outputs in some callback executions require publishing a status output as described in Callback Outputs after a callback is complete. Since this only entails publishing an additional message, this modification does not impede the node’s functionality in any way when not using the orchestrator. Nodes that fully deviate from the assumed callback behavior require appropriate modification before being suitable for use with the orchestrator, as was illustrated with the tracking and planning modules in ROS Nodes.

Creating the node configuration file does not present a significant effort for initial integration, but maintaining the configuration to match the actual node behavior is essential. Although the orchestrator can detect some mismatches between node behavior and description, omitted outputs and services can not be controlled by the orchestrator and might lead to nondeterministic system behavior.

While the model of ROS nodes that only execute ROS callbacks, which then publish at most one message on each configured output topic, is clearly not sufficient for all existing ROS nodes, it does apply to a wide class of nodes in use. Nodes such as detection modules and control algorithms often operate in a simple “one output for each input” way or are completely time triggered, executing the same callback at a fixed frequency. Such nodes are not part of this experimental setup, since the specific simulator in use already integrates the detection modules.

4.4. Application to Existing Scenario¶

In this section, the effect of using the orchestrator in the use case introduced in System Setup is evaluated. In the following, the ability of the orchestrator to ensure deterministic execution up to the metric-calculation step is demonstrated using both the simulator and recorded input data from a ROS bag, as well as combined with dynamic reconfiguration during test execution.

4.4.1. Simulator¶

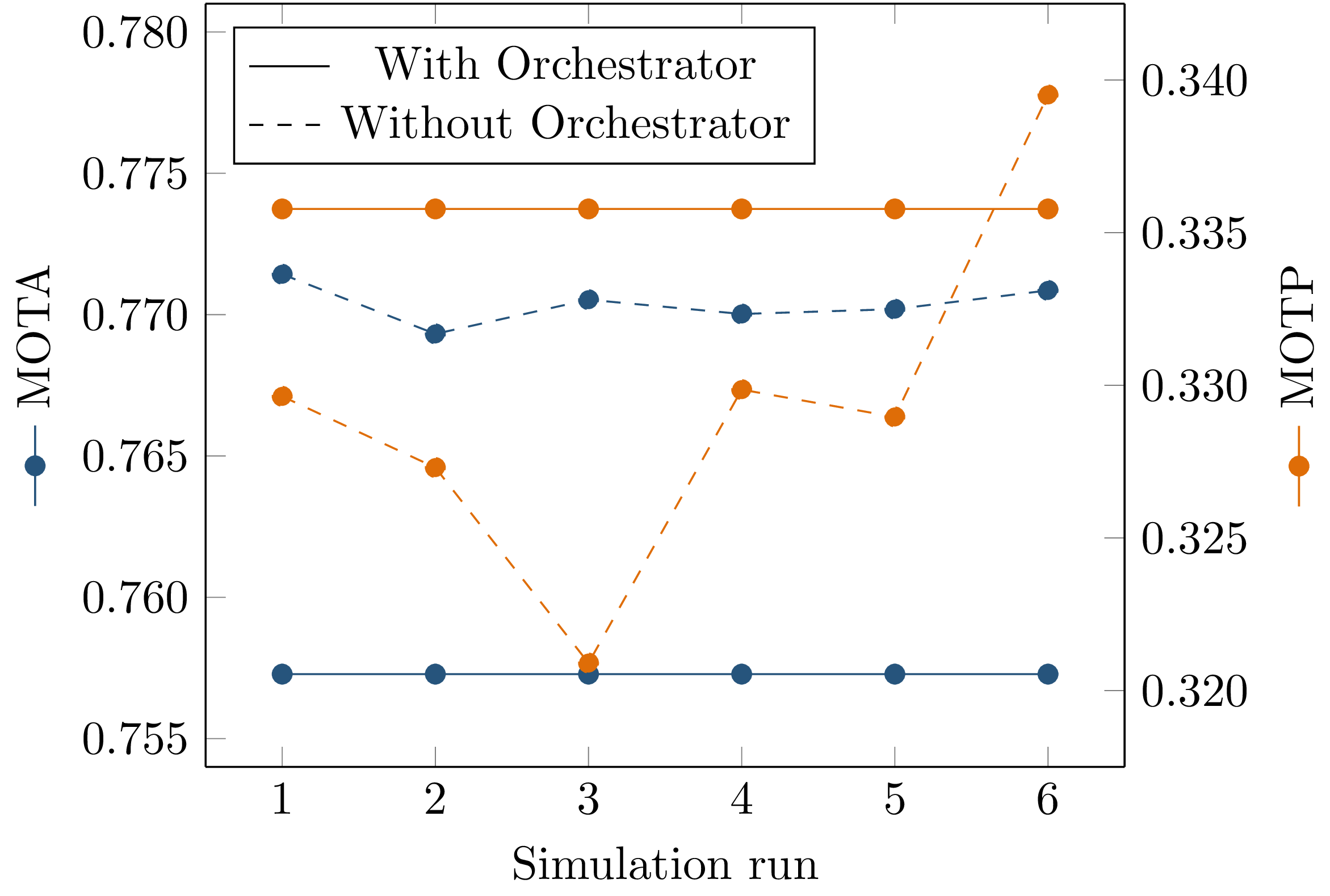

When evaluating the tracking module in the previously introduced scenario, the MOTA and MOTP metrics introduced in Software Performance Metrics in Autonomous Driving are calculated. To calculate these metrics, the tracking outputs are recorded together with ground truth data from the simulator during a simulation run. Those recordings are then loaded and processed offline. When running the evaluation procedure multiple times, it can be observed that the resulting values differ for each run, as shown in Fig. 4.9. This is due to nondeterministic callback execution during evaluation: Both the simulator and the trajectory planning module run independently of each other, and the callback sequence of the multiple inputs to the tracking module is not fixed.

Fig. 4.9 Evaluation of the MOTA and MOTP metrics in the scenario introduced in System Setup over multiple simulation runs, both with and without the orchestrator.¶

When running the simulation using the orchestrator, the variance in the calculated metrics is eliminated. This shows that in this example the orchestrator successfully enabled the use case of repeatable execution of test cases for evaluating a software module inside a more complex system.

Not only are the calculated metrics consistent, the deterministic execution as ensured by the orchestrator results in bit-identical outputs of the tracking module for every simulation run, and thus exact equality of the recordings generated. This enables additional use cases for testing such as easily comparing the output of the module before and after presumably non-functional changes are made to the source code. Previously, such a comparison would require parsing the recorded results, calculating some similarity measure or distance between the expected and actual results, and applying some threshold to determine equality. Now, simply comparing the files without any semantic understanding of the contents is possible.

4.4.2. ROS Bag¶

In order to test the use case of ROS bag replay, the player implemented in ROS Bag Player is used. Although the ROS bag player provides inputs in deterministic order, the characteristics of the input data are different from the simulator. During the recording of the ROS bag, the sensor input topics and pre-processing nodes are subject to nondeterministic ROS communication and callback behavior. This results in a ROS bag with missing sensor samples (due to dropped messages as well as unexpected behavior of real sensors) and reordered messages (due to nondeterministic transmission of the messages to the ROS bag recorder). All those effects would usually not be expected from a simulator, which produces predictable and periodic inputs.

This does not present a problem for the orchestrator: Since the callback graph construction is incremental for each input, the only a priori knowledge the orchestrator requires is the API call from the data provider informing the orchestrator of the next input, and the node and launch configurations to determine the resulting callbacks. Specifically, the orchestrator does not require information such as expected publishing frequencies or periodically repeating inputs at all.

In order to reuse the existing test setup, a ROS bag was recorded from the outputs of the simulator. To simulate the effects described above, the ROS bag is manually modified by randomly dropping messages and randomly reordering recorded messages.

Using the multi-object tracking module was not possible, however, since the high rate of dropped messages causes a callback behavior that can not be modeled by the node configuration as introduced in Node Configuration. In addition to the behavior described in Tracking Module of zero or one output for each measurement input, certain combinations of inputs may cause multiple outputs from one input callback. This is due to a sophisticated input queueing approach, that forms batches of inputs with small deviations in measurement time, that only get processed once a batch contains measurements of all sensors. In case of missing measurements, a newer batch might be complete while older, incomplete batches still exist. The queueing algorithm assumes in that case that the missing measurements of the old batches will not arrive anymore (ruling out message reordering, but allowing dropping messages), and processes the old batches, producing multiple outputs in one callback. Handling more outputs than expected is not possible for the orchestrator since the orchestrator must determine when a callback is completed to allow the next input for the corresponding node. If a callback publishes additional outputs after it is assumed to have been completed already, the orchestrator can not identify the source of the additional output or wrongly assigns the output to the next callback expected to publish on the corresponding topic.

This queueing also makes the tracking module robust against any message reordering between the ROS bag player and the module itself, resulting in deterministic execution even without the orchestrator and at high playback speed. When using a ROS bag with reordered, but without dropped messages, the experimental setup can be verified and performs as expected with a ROS bag as the data source instead of a simulator, which also shows that the orchestrator can successfully be used in combination with existing node-specific measures to ensure deterministic input ordering. The further behavior of the orchestrator remains unchanged, meaning nondeterminism in larger systems under test such as the cases demonstrated in Verification of Functionality is prevented.

Furthermore, when using ROS bags as the data source it may be possible to easily maximize the playback speed without manually choosing a rate that does not overwhelm the processing components causing dropped messages. More details on this specific use case will be given in Execution-Time Impact.

4.4.3. Dynamic Reconfiguration¶

To test the orchestrator in a scenario including dynamic reconfiguration, the previous setup was extended by such a component. Since a module for dynamic reconfiguration of components or the communication structure was not readily available, a minimal functional mockup was created: A “reconfigurator” component with a periodic timer callback decides within this callback if the system needs to be reconfigured, and then executes that reconfiguration. The node description for the reconfiguration node is given in cref{listing:eval:reconfig:node_config}. In this example, the reconfiguration reduces simulated measurement noise, which could simulate switching to a more accurate, but also more computationally demanding perception module. The mock reconfigurator always chooses to reconfigure after a set time. A real working counterpart would require additional inputs such as the current vehicle environment, which are omitted here.

1{

2 "name": "sil_reconfigurator",

3 "callbacks": [

4 {

5 "trigger": {

6 "type": "timer",

7 "period": 1000000000

8 },

9 "outputs": [],

10 "may_cause_reconfiguration": true

11 }

12 ]

13}

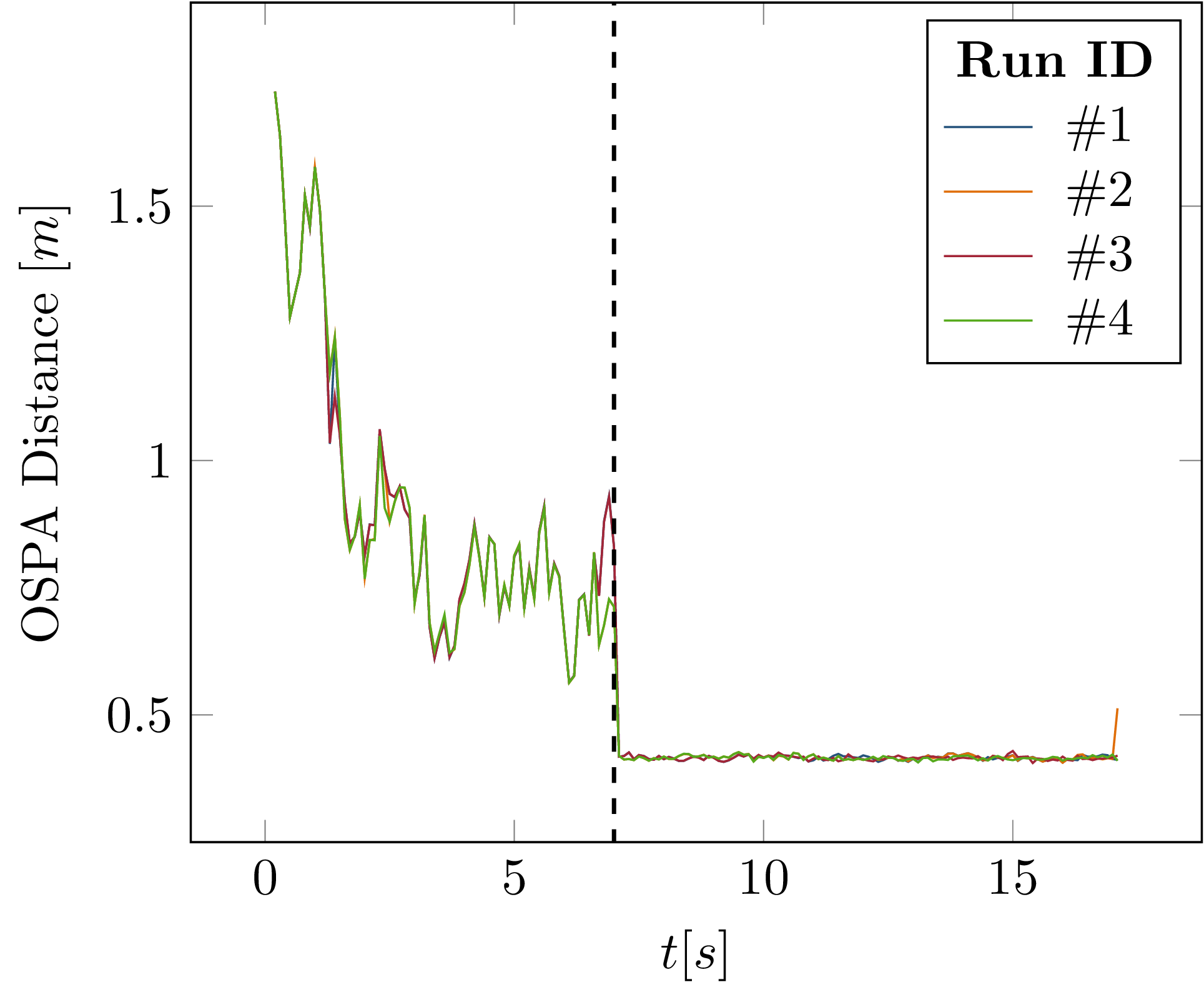

Fig. 4.10 OSPA distance of tracks versus ground truth during multiple simulation runs. The dashed vertical line marks the timestep in which the runtime reconfiguration occurs.¶

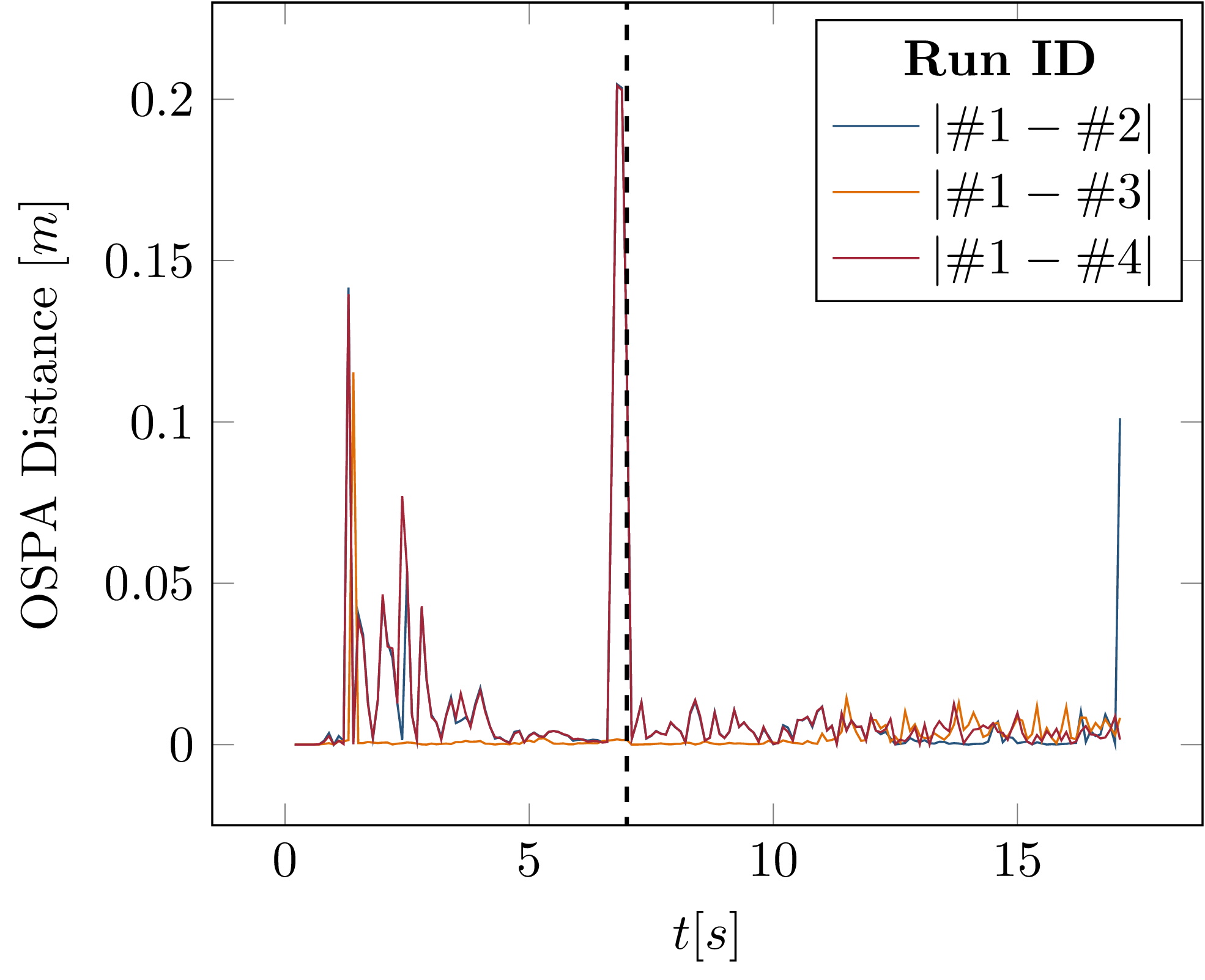

Fig. 4.11 Absolute difference in OSPA distances between the simulation runs. The dashed vertical line marks the timestep in which the runtime reconfiguration occurs.¶

Fig. 4.10 shows the OSPA distance (see Software Performance Metrics in Autonomous Driving) between the tracking result and the ground truth object data from the simulator over multiple simulation runs. The OSPA distance was chosen as a metric in this case since it is calculated for every time step instead of as an average over the entire simulation run, as is the case with the MOTA and MOTP metrics used above. This allows evaluation of how the metric changes during the simulation run and clearly shows the reconfiguration step. It is apparent that the reconfiguration module successfully switched to a lower measurement noise at \(t=7s\). Importantly, however, the evaluation results of the multiple runs do not completely overlap. This is again due to nondeterministic callback execution within the tracking, planning, and simulator modules. The differences between the runs, plotted in Fig. 4.11, show that all runs deviate from the first run, with two runs showing the largest difference at the exact time of reconfiguration.

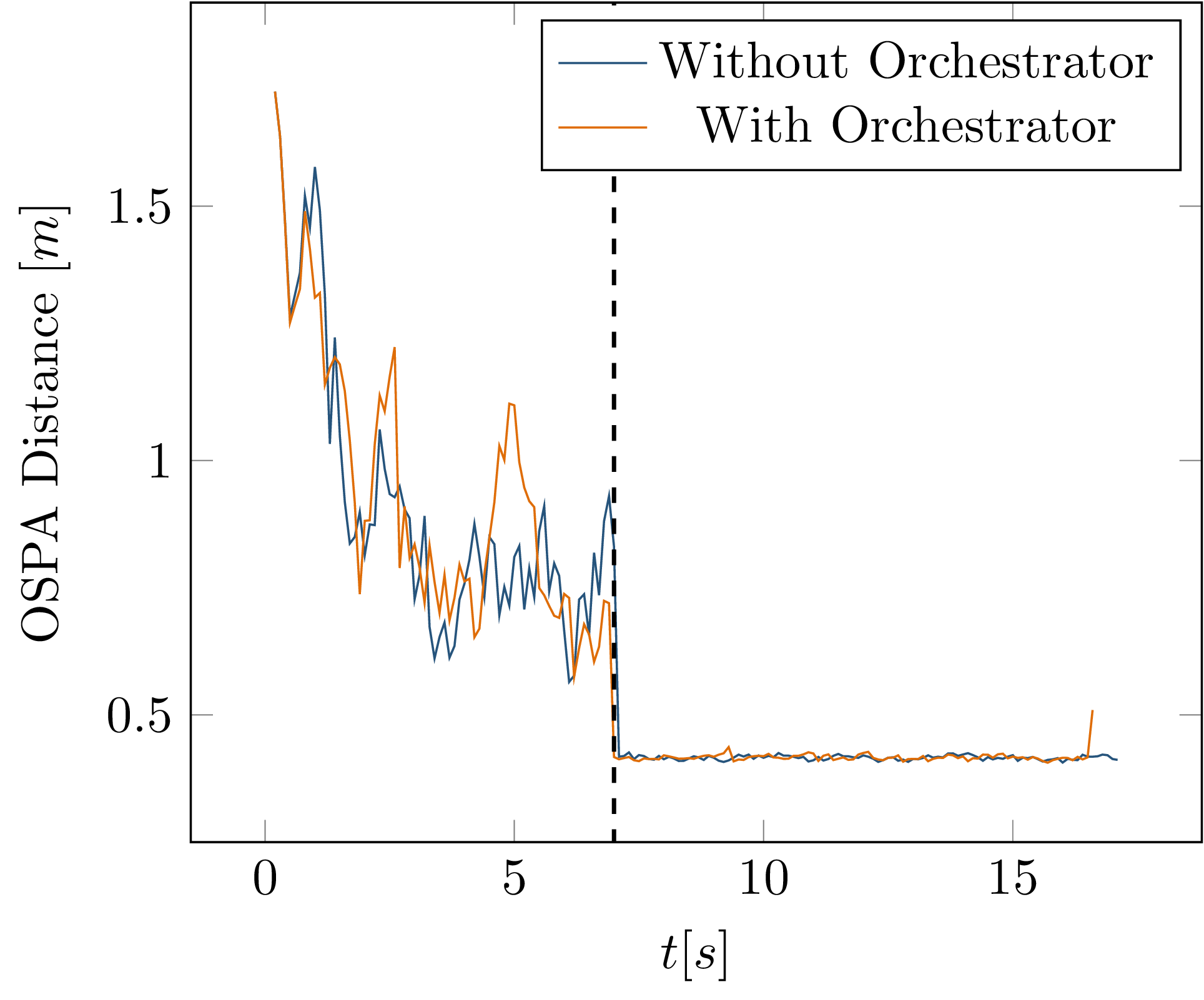

Fig. 4.12 OSPA distance of tracks versus ground truth over time, comparison between initial simulation run and simulation while using the orchestrator.¶

Using the orchestrator, the measured tracking result does differ from the previous simulation runs, as shown in Fig. 4.12. The output is however deterministic and repeatable, even if a reconfiguration occurs during the simulation. Again, this demonstrates the successful application of the orchestrator framework, even in the presence of dynamic reconfiguration at runtime.

4.4.4. Discussion¶

In Application to Existing Scenario, the successful implementation of two design goals was verified: First, Simulator and ROS Bag demonstrate successful use of the orchestrator with both a simulator and ROS bag as data sources. Notably, no additional requirements are placed on the specific ROS bag used, allowing the use of the orchestrator with already existing recorded data. Secondly, Dynamic Reconfiguration shows that the guarantees of the orchestrator hold when the system is dynamically reconfigured at runtime. These tests represent exactly the use case of evaluation of a component within a larger software stack that motivated this work, that is able to run repeatedly and deterministically using the orchestrator.

In ROS Bag, a limitation of the orchestrator in terms of modeling a node’s output behavior was reached. In order to use such nodes with the orchestrator in the future, an extension to the current callback handling might be required and is proposed here: A solution to this problem might be to allow the node to publish a status message after every callback, which specifies the number of outputs that have actually been published in this specific callback invocation. This would allow the orchestrator to ensure the reception of every callback output, and prevent wrong associations of outputs to callbacks. As additional messages on the corresponding topics would also cause additional downstream callbacks for subscribers of those topics, this approach might however introduce additional points of synchronization across the callback graph.

4.5. Execution-Time Impact¶

Due to the required serialization of callbacks and buffering of messages, a general increase in execution time is to be expected when using the orchestrator. In the following, this impact is measured for a simulation use case and the individual sources of increased execution time, as well as possible future improvements, are discussed.

4.5.1. Analysis¶

To measure the impact of topic interception, the induced delay of forwarding a message via a ROS node is measured. In order to compensate for latency in the measuring node, the difference in latency for directly sending and receiving a message in the same node versus the latency of sending a message and receiving a forwarded message is measured. When using a measuring and forwarding node implemented in Python and using the “eProsima Fast DDS” middleware, the latency from publishing to receiving increases from a mean of 0.64 ms to 0.99 ms. This induced latency of 0.35 ms on average is considered acceptable and justifies the design choice of controlling callbacks by intercepting the corresponding message inputs.

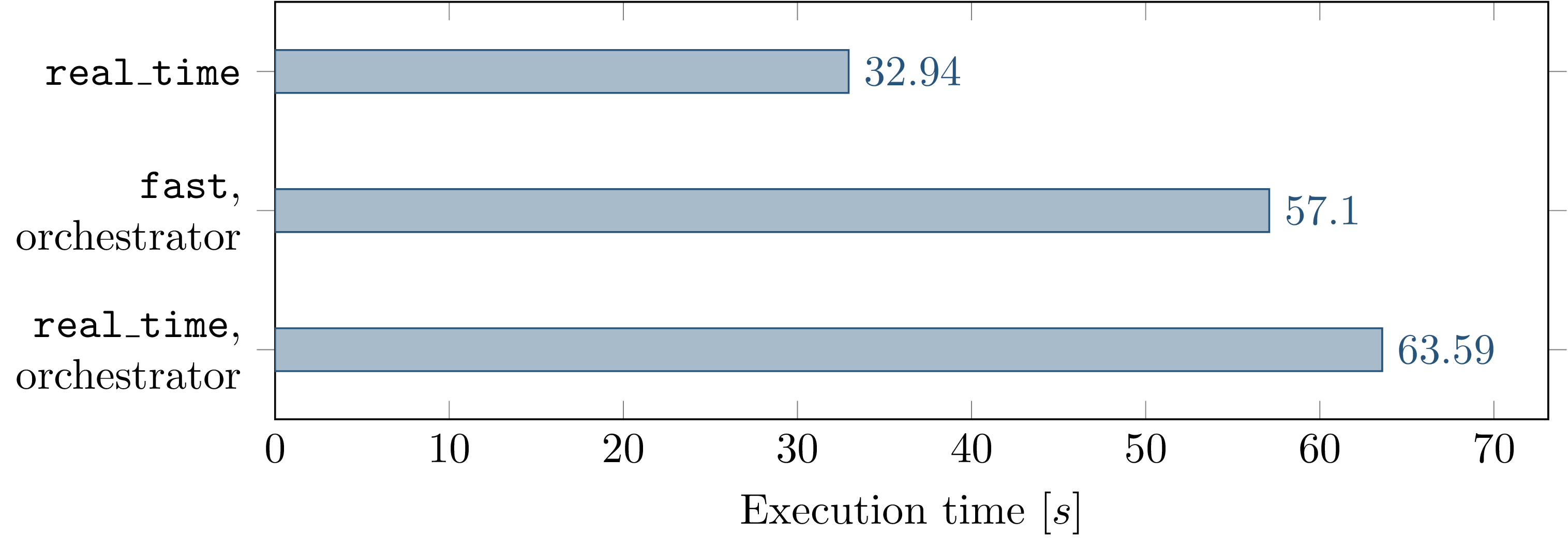

Fig. 4.13 Comparison of execution time for one simulation run between not using the orchestrator, using the orchestrator with faster than real-time execution, and using the orchestrator with real-time execution.¶

Fig. 4.13 shows a comparison of execution time for one simulation run of the scenario introduced in System Setup. The first bar shows the runtime without using the orchestrator, the bottom two bars show the time when using the orchestrator.

The simulator currently offers two modes of execution:

fast executes the simulation as fast as possible, while real_time slows down the simulation to run at real-time speed if the simulation itself would be able to run faster than real-time.

Using the fast mode is only appropriate combined with the orchestrator or some other method of synchronization between the simulator and software under test.

If the simulator is not able to run in real-time, deliberate delays to ensure real-time execution should already be zero.

Since Fig. 4.13 still shows an increase in runtime for using the real_time mode compared to the fast mode, the orchestrator is considered with the fast execution mode in the following.

Nonetheless, it is apparent that the orchestrator causes a significant runtime impact as the execution time is increased by about 73% in the fast case.

Evaluating the orchestrator itself for execution time, it can be found that during a simulation run, the callback for intercepted message inputs runs on average 0.6 ms, and the callback for status messages runs 0.9 ms. The API functions for waiting until publishing a time or data input execute in 0.9 ms and 0.5 ms. This sums up to more than 12.3 seconds spent executing interception and status callbacks, which in this scenario happens within the simulator. The simulator furthermore spends about 5 seconds executing orchestrator API calls.

The remaining increase in execution time is explained by serializing the execution of dependent callbacks. The vehicle tracking and planning components may both call the ego-motion service, which prevents parallel execution. The speed of publishing inputs by the simulator is greatly reduced especially for nodes like the tracking module, which has a relatively large number of inputs (12, in the evaluated examples) that are published sequentially. This would usually happen without waiting, but the orchestrator requires confirmation from the tracking module that an input has been processed before forwarding the next input to ensure a deterministic processing order.

Finally, the orchestrator requires the simulator to receive and process the output from the planning module before advancing the simulation.

This is realized by the changes_dataprovider_state flag for the corresponding callback in the node configuration file, which causes the wait_until_dataprovider_state_update_allowed API call to block until the callback has finished.

For any simulator, the “dataprovider state update” corresponds to executing a simulation timestep, which results in an effective slowdown of each simulation timestep to the execution time of the longest path resulting in some input to the simulator.

The other available flag for callbacks, may_cause_reconfiguration, presents a similar point of global synchronization:

This flag is applied to callbacks of a component that may decide dynamically reconfigure the ROS system, as described in Dynamic Reconfiguration, based on the current system state (such as vehicle environment, in the autonomous driving use case).

To ensure that the reconfiguration always occurs at the same point in time with respect to other callback executions at each node, any subsequent data inputs and dataprovider state updates must wait until either the reconfiguration is complete or the callback has finished without requesting reconfiguration.

This presents an even more severe point of synchronization, since it immediately blocks the next data inputs from the simulator, and not only the start of the next timestep, while still allowing to publish the remaining inputs from the current timestep.

4.5.2. Discussion¶

Using the orchestrator significantly increased execution time in the simulation scenario. To reduce the runtime overhead caused by the orchestrator, multiple approaches are viable. As significant time is spent executing orchestrator callbacks and API calls, improving the performance of the orchestrator itself would be beneficial. A possible approach worth investigating could be parallelizing the execution of orchestrator callbacks. Both parallelizing multiple orchestrator callbacks and running those callbacks in parallel to the host node (the simulator or ROS bag player) could be viable. In addition to a more efficient implementation of the orchestrator itself, the overhead of serializing callback executions is significant. While some of that overhead is inherently required by the serialization to ensure deterministic execution, it has already been shown in Multiple Publishers on the Same Topic, Parallel Service Calls that parallelism of callback executions can be improved with more granular control over callbacks, their outputs, and service calls made from within those callbacks.

When using a ROS bag instead of a simulator as the data source, some of the identified problems are less concerning.

Since a ROS bag player does not have to perform any computation and reading recorded data is not usually a bottleneck for performance, the overhead of the orchestrator API calls is less problematic.

Furthermore, without closed-loop simulation, the wait_until_dataprovider_state_update_allowed API call is not necessary which has been identified as a factor that reduces the potential for parallel callback execution.

In some scenarios, the use of the orchestrator is even able to improve execution time:

When replaying a ROS bag, the speed of playback is often adjusted.

Use cases for playing back a recording at equal to or slower than real-time occur when the developer intends to use interactive tools for introspection and visualization such as for debugging the behavior of a software component in a specific scenario.

Often, however, the user is just interested in processing all messages in the bag, preferably as fast as possible.

The playback speed is thus adjusted to be as fast as possible while the software under test is still able to perform all processing without dropping messages from subscriber queue overflow.

This overflow however is usually not apparent immediately, and processing speed may depend on external factors such as system load, which makes this process difficult.

When using the orchestrator, however, the processing of all messages is guaranteed and queue overflow is not possible.

This allows the ROS bag player to publish messages as soon as the orchestrator allows, without specifying any constant playback rate.

Playing a ROS bag is necessarily an open-loop configuration without any synchronization for dataprovider state update, and the player itself is expected to have a fast execution time when compared to the ROS nodes under test.

If a speedup is achieved in the end depends on if the remaining overhead from serializing callback invocations outweighs the increased playback rate or not.

The design goal of minimizing the execution time impact is thus only partially achieved. As measured in this section and detailed in Discussion, the serialization of callbacks and thus the induced latency of executing callbacks is not minimal. The runtime of the orchestrator component itself has been shown to be significant as well, although this was not the bottleneck in this test scenario.